LUIS VICENTE LEÓN

This article I mentioned a long time ago, but its validity is perfect. We remember about the intervention of bakeries.

Some think that the embarrassing history of the price controls of the Greeks, analyzed impeccably by Angel Alayon in Prodavinci several years ago, should have been sufficient for the world to understand the inadequacy and uselessness of that measure. But history has shown us that the error has been repeated over and over, even though the result has always been disastrous.

Let’s return to the story that Angel tells us, now displaced to Zimbabwe in the 21st century.

“Imagine an economy where prices double every day. At that damn pace grew inflation in Zimbabwe. The official figure for 2008 reached the illegible figure of two hundred and thirty-one million percent per year (231,000,000,000%). Money was worth nothing and citizens survived amid one of the most feared economic phenomena: hyperinflation. But let’s get the Zimbabwe movie back eight years and let’s go back to 2000.

Since the beginning of 2000, Zimbabwe had suffered the consequences of the divestment that had involved the confiscation of land from white landowners and an expansionary monetary policy. Prices began to rise, at first with some timidity, reaching by the year 2000 a 54%. Five years later, prices rose to 585.4% per annum and by 2006 prices broke the barrier of the thousand.

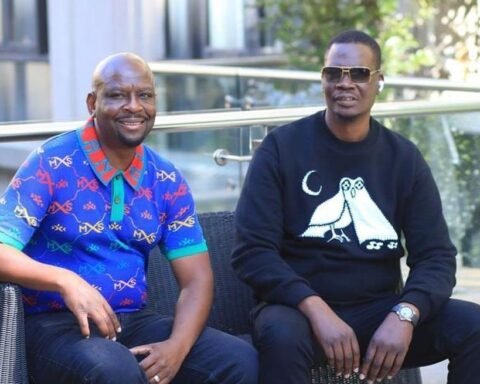

Robert Mugabe faced a dilemma and decided to prosecute traders blaming them on the inflationary process. In December 2006, Burombo Mudumo and Lemmy Chikomo of Lobels Bakery were sentenced to four months in prison for selling bread above regulated prices. The sentencing magistrate said that “imprisonment should serve as a warning to other potential violators of the Act.” The bakers, now in prison, argued in their defense that they had sent letters to the ministries in charge of price regulation warning them that if they sold at the established prices they would be forced to stop production. They never received an answer and, in the dilemma, decided to produce and sell. They did not believe that they would be punished with the loss of their freedom, but behind bars they saw each other.

Prices accelerated its rise, so Mugabe decided to take action on the issue and decided to ban inflation. Yes, read well: prohibit inflation. It issued a decree that required the immediate reduction of all prices in the economy by fifty percent (50%), and after that extraordinary price reduction, no one could raise them again.

Mugabe’s policy had immediate consequences: in just one weekend, consumers exhausted all stocks of food and appliances. On Monday morning, businesses were empty and a few merchants awoke behind bars for alleged speculation and hoarding. From that moment it was practically impossible to get meat, salt, sugar, bread, milk or oil in Zimbabwe. Economists gave up the idea of measuring inflation for one reason: prices were irrelevant, there were no products.

The situation in Zimbabwe has improved since 2009. Mugabe accepted the use of foreign currency as a means of payment and began a process of price release. It has even given signs of allowing the return of the former landowners to their lands. Zimbabwe is a country that continues to err in a complicated political and economic labyrinth, but, paradoxically, it now walks it taken from the hand of the International Monetary Fund, its former enemy.