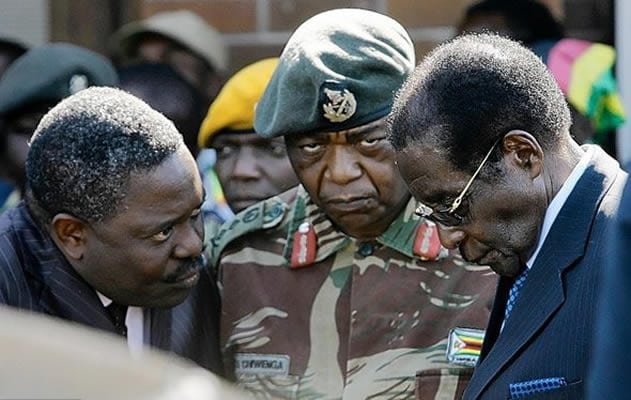

President Robert Mugabe recently railed at top officials in the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) for meddling in Zanu PF’s internal affairs, hinting he might retire the meddlesome security commanders.

He told multitudes of Zanu PF supporters in his home province of Mashonaland West in Chinhoyi two weeks ago that “politics led the gun”, some in the uniformed forces were positioning a candidate to succeed him.

“We give immense respect to our defence forces. Most of those in leadership are persons we were with outside the country and we continue to respect them as revolutionaries,” he said.

“Yes, they will retire and we must find room for them in government so they don’t languish, so they continue the struggle now, political struggle together with all of us in the leadership of the country and this is what we expect to happen.”

Mugabe, one of the last from a political generation that included the late South African president Nelson Mandela, was confirmed at the Zanu PF conference in Masvingo last year as the presidential candidate for the next presidential election in 2018, when he will be 94.

The next Zanu PF elective congress is in 2019, when a new leader will be chosen.

While the security establishment is deeply loyal to Mugabe, whom they see as a steadying hand amid intense jockeying over his succession in the State and the ruling party, top commanders are said to be backing Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa to succeed him.

Political analysts this week said while Mugabe may not be happy with how his military chiefs have gotten entangled in Zanu PF’s politics that may not change the fact that the army has emerged as a major Zanu PF power broker in the governing power — rightly or wrongly.

Blessing Miles Tendi, an Oxford scholar, asserts that Mugabe has maintained civilian control over the military through shared ideology, patronage, and the formal and informal power he gets from his position as commander-in-chief and being the most senior remaining figure from Zimbabwe’s nationalist liberation struggle.

As a reward for their loyalty, Mugabe has given security sector officials high-level positions throughout the State and party and also granted the military and other security sector officials choice farms.

When it suits him, Mugabe has even allowed the military to issue statements, lampooning his political rivals, especially Morgan Tsvangirai’s MDC.

In the bloody 2008 elections, Zanu PF’s rivals were bitter that the military had become partisan — fighting in the ruling party’s corner.

More and more, top military chiefs have been pushing the boundaries to the point of taking sides in the on-going debate on Mugabe’s succession.

Piers Pigou, senior consultant at the International Crisis Group, said it would not be unusual for military chiefs to be retired, adding that most of the security force chiefs have been retained on rolling annual contracts for some years now.

“As such, Mugabe has retained the option of retiring senior security figures for some time now. His direct reference to retiring these commanders is sufficiently opaque to keep his options open on the timing; it could be interpreted as a threat to remind, as his reference to accommodating them in government could be interpreted as an olive branch. Once again, we see Mugabe keeping his options open, although he had never been so publicly explicit about these retirements,” said Pigou.

United Kingdom-based politics expert, Stephen Chan, said Mugabe “has to do this very, very carefully because those generals provide a very great deal of political strength.”

“Having said that it’s normal in militaries around the world for generals to be retired at a certain age. This is so that there be can a constant dynamic renewal in the military,” he said.

“The first role of the military is to defend the country. And you have to have leaders that are absolutely up to date with modern ways of conducting the defence of the country.

“Even in Great Britain, the most senior generals get one term at the top and they are replaced in what they call the chairman of the defence staff and then they have to go. So this would not be abnormal. However, here it’s a dangerous political game.”

With Mugabe’s wife Grace emerging as a potential successor to the veteran president after openly challenging her husband at a women’s league national assembly meeting in Harare two weeks ago to name his preferred heir, experts are warning that if the incumbent passes the reins to a successor that is not acceptable to the military it may backfire.

This comes as brawling over the leadership of a post-Mugabe Zanu PF has sharply escalated, with two bitterly opposed camps going hammer and tongs against each other, with one rooting for Mnangagwa, 74, and the other backing Grace, 52, who has become a potent political force.

Defence minister Sydney Sekeramayi is also being tipped as a deserving successor to Mugabe.

Alexander Noyes, a senior associate at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said if Mugabe dies in office or passes the reins to a successor, the chances of some form of backlash could increase significantly, especially if the winning candidate does not enjoy support from the military.

“In this scenario, with Mugabe no longer on the scene, . . . (Constantino) Chiwenga or others may choose to step in and install Mnangagwa, a fellow liberation war veteran, or another leader who will secure their interests,” said Noyes.

In his address in Chinhoyi, an exasperated Mugabe suggested he would never back any leader who jockeys for his post while he was still there.

This comes as the women’s league has stepped up pressure demanding the reinstatement of a constitutional clause scrapped at the 2014 congress prescribing the installation of a female vice president, amid claims this was part of well-choreographed move to replace Mnangagwa with Grace.

With the fluid politics in Zanu PF, analysts said Mugabe is under immense pressure to dethrone Mnangagwa and his allies in the top echelons of the security establishment and replace them with “acceptable” individuals within the army, and further install Sekeramayi as successor, with Grace as one of the vice presidents.

This comes as Sekeramayi’s political stock is rising amid indications that neutrals in the do-or-die Zanu PF war to succeed Mugabe are pushing for his elevation to occupy the top office in the event that the incumbent retires or gets incapacitated.

Pigou said: “There is some speculation that Sekeremayi’s elevation is part of a longer term plan to facilitate Grace Mugabe’s political ambition. This seems an unlikely scenario.

“Indeed her leverage will diminish considerably once her husband has left the political scene. It is difficult to see how any political force within Zanu PF will see her as a significant asset once Mugabe is gone.

“Much depends on whether the political forces around her feel that a leadership role for the first lady will translate into a strengthened position for themselves or whether they would see her as a liability. The question must be asked, what does she bring to the table?”

Given Mugabe’s apparent advanced age and increasing frailty, analysts warned this raises the spectre of the president’s natural wastage while in office and the attendant risk of backward slippage towards political disorder and economic collapse.

Mugabe told the Chinhoyi rally he was OK health-wise.

Pigou said it was highly unusual for someone to retain this high office at such an advanced age.

“It is clear Mugabe no longer has the strength to provide the kind of leadership required given Zimbabwe’s acute challenges; his frequent dozing off at public events, his struggling gait, slow and mumbling delivery are all signs that do not inspire confidence and strongly suggest his stubborn retention of office reflects an inability to face reality and let go,” told the Daily News on Sunday.

Were Mugabe to be incapacitated, resign, removed from office or die, the new Constitution states that until 2023, the vice president who last acted as president assumes office as president for the next 90 days until the party nominates a replacement for consideration by Parliament.

Pigou said it remains unclear exactly how Zanu PF will make its selection as the modalities of the special congress that is tasked with making this decision are not explicitly set out in the party’s constitution.

Amid fears this may see someone from outside the party presidium leapfrogging into State House, Pigou said: “A selection outside of the presidium is a possibility but will be contingent on dynamics both within and outside the party’s structure. It remains to be seen whether Zanu PF will be able to demonstrate a credible internal democratic process.”

Dailynews