For the past two months, Elsie, a South African community health worker, has been receiving desperate calls from HIV-positive children she can no longer assist. Due to US funding cuts, she is now unable to support them.

The 45-year-old, who asked to remain anonymous, previously worked in Msogwaba township, around 300km (190 miles) east of Johannesburg. She was part of a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that provided care to nearly 100,000 people annually, including HIV-positive children and orphans. The organisation relied on over $3 million in annual funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

However, since former US President Donald Trump reduced foreign aid in early 2023, Elsie and over 100 other health workers have been left unable to continue their work. “I was supporting 380 children, ensuring they took their medication and were not discriminated against,” she said. “Now, I can do nothing.”

South Africa has one of the world’s highest HIV/AIDS rates, with 7.8 million people—about 13% of the population—living with the virus. The government has assured that antiretroviral (ARV) treatment will continue, with plans to extend treatment to 1.1 million additional patients by year-end.

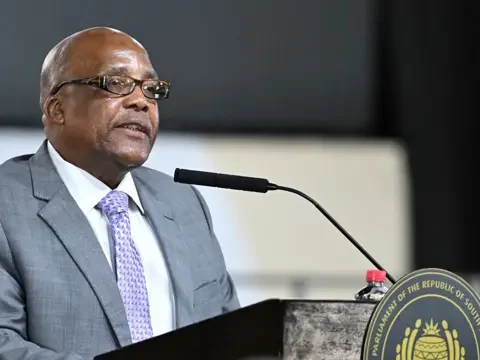

“The country has the capacity to provide HIV treatment,” said health department spokesperson Foster Mohale. Almost 90% of ARVs are funded through government budgets. However, the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) cuts have removed key prevention, counselling, and monitoring programmes, which make up 17% of South Africa’s overall HIV response.

“It’s about more than just medicine,” said Sibongile Tshabalala-Madhlala, chairperson of the Treatment Action Campaign, a leading HIV advocacy group. “It’s about people receiving support, being encouraged to stay in care, and preventing new infections.”

The loss of funding has also worsened staff shortages in overcrowded hospitals. The cuts have already led to the dismissal of 15,000 healthcare workers, according to Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi.

A study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggested that eliminating all PEPFAR funding in South Africa could result in over 600,000 additional HIV-positive patients dying within a decade. While the Department of Health dismissed these figures as “assumptions,” activists fear the worst.

“People will die,” Tshabalala-Madhlala warned. “Some are already sharing medication, while others will miss doses because they can’t take time off work. This will lead to higher infection rates and more deaths.”

One affected individual is a 17-year-old boy from Msogwaba. Sitting in his mother’s home, he expressed distress about missing his next clinic appointment. Previously, Elsie would accompany him, ensuring he received his medication on time. His mother, who cannot afford to take time off work, said, “I feel like we’ve been abandoned.”

Elsie shares that sentiment. “I was forced to abandon them. They trusted me, and now I can’t help.”