Las Vegas had spent years planning for the worst: training its police force according to an anti-terrorism protocol it adopted in 2009 to respond to mass shootings, chemical attacks, suicide bombings, and planes flying into buildings, according to city officials and security professionals.

But when it came to Sunday night’s attack that killed 58 people and wounded hundreds more at an open-air concert in the city, police found themselves with few options to stop the gunman quickly, they said. It underscored the difficulty American cities face in protecting citizens from attacks that can take unpredictable forms.

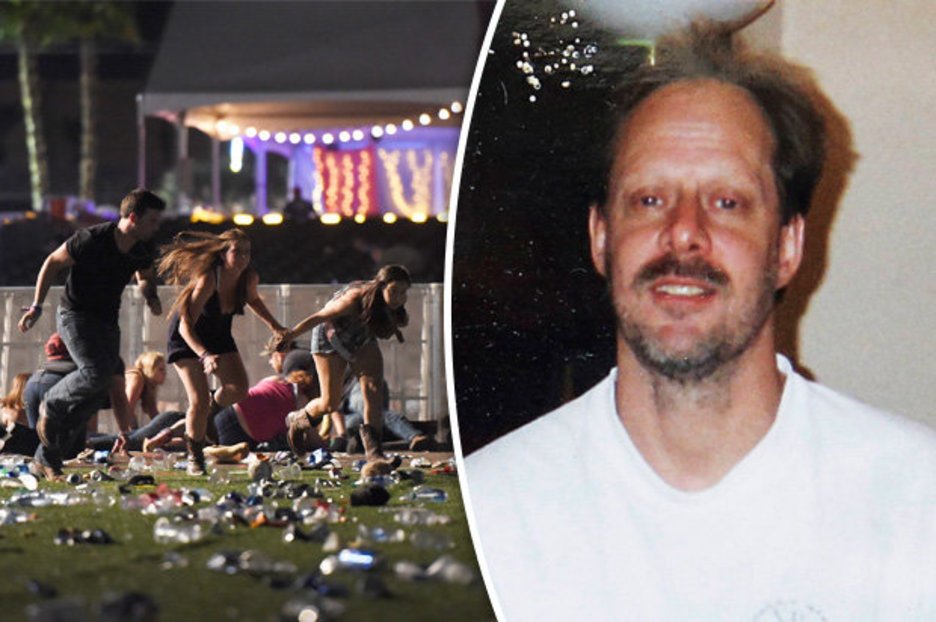

Firing from the 32nd floor of a hotel near the city’s world famous neon-lit Strip, at night, at a range of 500 yards with an arsenal of high-velocity semi-automatic weapons modified to shoot rapidly, gunman Stephen Paddock had pulled the city into a nightmare that left him virtually unopposed for crucial minutes, with police unable to safely return fire.

The angles, the distances, and the presence of thousands of people made it impossible, they said.

“Our officers showed incredible restraint. They can fire that distance. It’s not safe to do so,” said Robert Chamberlin, a member of the Las Vegas police department’s counter-terrorism force. “You are firing 32 floors up, from 500 meters (yards). So the trajectory of our rounds…even if we were accurate, they’re going to go up into the ceiling, up into the next floor.”

“(Our officers) knew they had to close so that’s what they did,” he said.

Paddock sprayed bullets continuously on the concert crowd of 22,000 people for about 10 minutes, starting at 10:05 p.m. PT (7:05 p.m. ET), according to Clark County Sheriff Joseph Lombardo. Police blew open Paddock’s hotel room door 75 minutes after the shooting started, finding he had killed himself.

Paddock’s attack was only the second major mass shooting in modern U.S. history where the gunman fired from an elevated position, according to David Shepherd, a former FBI agent who advises the Las Vegas police department on security issues.

The last one that inflicted large numbers of casualties was at the University of Texas in 1966 when a gunman in a tower killed 15 people and wounded 31 during an attack that lasted 96 minutes.

In 2009, the Las Vegas police adopted a new, military-style, counter-terrorism plan and training, called MACTAC, or Multi-Assault Counter-Terrorism Action Capabilities and intended to help it deal with attacks. Officials said it was instituted as a response to the attack on Mumbai, India a year earlier in which al Qaeda-linked militants killed 166 people in a series of coordinated shootings and bombings over four days.

The protocol required every law enforcement officer from every department in the region to be trained in the same way to respond to attacks, members of the MACTAC team told Reuters in an interview this week. This training allowed security personnel from different departments to team up quickly, form small units, and – in the case of a shooting – to direct fire at the shooter’s location from different angles.

On Sunday, Paddock’s high perch in a hotel filled with people complicated the well-trained response – first, because it was hard to exactly pinpoint his location, and second because of the dangers to bystanders if the police fired back.

“It did cause some challenges logistically, being outgunned like that,” said Lieutenant Reggie Rader, one of the MACTAC team members. He said officers did their best to get as quickly as possible to the hotel room from which Paddock was firing.

City councilmen Ricki Barlow and Steve Seroka praised the police for how they responded to Sunday’s attack, but admitted the shooter proved a difficult adversary, and that being prepared for every kind of attack is hard.

“Someone shooting high down into a crowd – of course we have looked at that. But the question becomes – how do you guard against that?” said Barlow.

Seroka said that many hotels in Las Vegas are equipped with technology to detect projectiles like cigarette butts coming off balconies and to pinpoint the room, but said there are no balconies at the Mandalay Bay hotel where Paddock had set up.

Seroka, a former U.S. Air Force colonel and veteran of both Gulf Wars, lamented the length of time Paddock ultimately had to shoot at the crowd. “Nine minutes is an eternity when you are taking fire,” he said.

But he added: “There is an old saying: no plan survives the first contact with the enemy. You cannot anticipate every possibility.”